Chernobyl tourism leaves no soul untouched

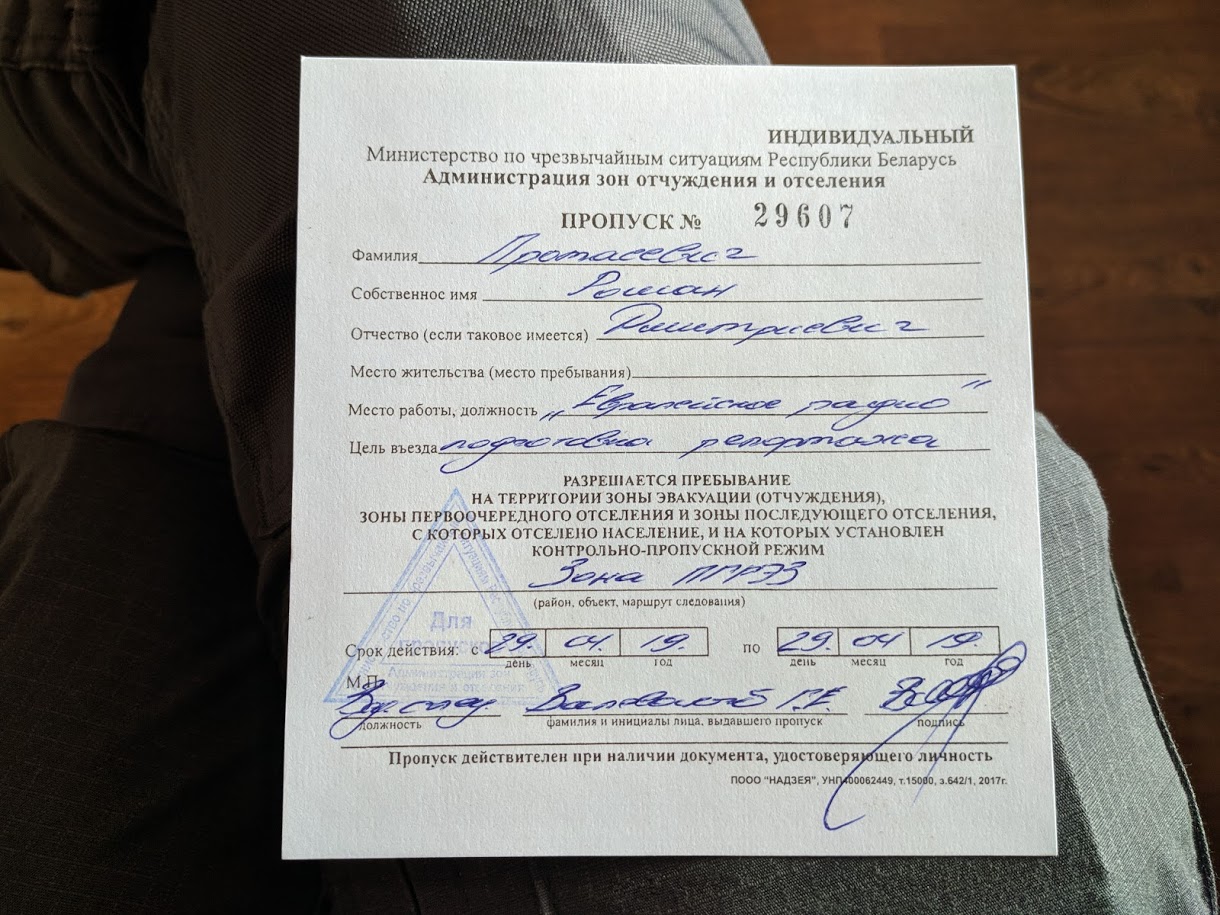

Raman Protasevich, Euroradio

In early April 2019 or 33 years after the Chernobyl nuclear power plant tragedy, Belarus opened the Exclusion Zone for tourists. The journey to the Zone begins in Khoiniki - a city where university graduates are afraid to end up after the mandatory workplace assignment. The administration of the Palessye State Radiation-Ecological Reserve (PSRER), operates from here.

The area of the reserve zone is more than 216 thousand hectares. Another 260 thousand hectares of the "Chernobyl" land is on the Ukrainian side of the border.

Euroradio journalist Raman Pratasevich has twice visited the Zone with scrappers aka stalkers. This time around, he went on an 'official' tour in order to compare his impressions. Here is what he has come back with.

These trips are not tourism

For a permit to visit the Exclusion Zone, you need to contact the Ministry of Emergency Situations. If you want to get into the Zone privately, a request with a justification of the reasons needs to be sent to the administration of the resettlement and exclusion zones of the Ministry of Emergency Situations. For organized tours everything is easier -- there is no need to substantiate anything, the documents will be prepared for you.

The tour starts in Khoiniki. It is here, on the outskirts of the city, that the administration of the Palessye State Radiation and Ecological Reserve is located. Here, experts check all necessary permits and, if all is well, give the final permission to visit the reserve, where the Exclusion Zone is located.

Having received the final paper permission, we meet with Maksim Kudzin, deputy director of the scientific unit of the reserve. Together with him, we go to the nearest checkpoint of the Exclusion Zone which is located in the village of Babichy. On the way, we learn that the territory of the Exclusion Zone is not getting smaller with time. On the contrary, it is expanding.

The reserve is under the supervision of 6 agencies at once. If there are "issues" with all the responsible agencies, a fine can reach $ 25 thousand. This is one of the reasons why there are many fewer stalkers in the Belarusian Zone than in the Ukrainian part. The 'stray' ones are usually caught on the railway tracks -- a well-known route that can lead you almost to the Chernobyl NPP itself just within a few hours.

Maksim notes: "There have always been official visitors in the reserve. Guided tours were conducted for officials, some students and foreign delegations. Now access is open to other visitors.

“Such trips mustn't be called tourism,” says Maksim Kudzin. "First of all, you need to understand what tourism is. Tourists are people who would stay here for a long time. We cannot do this, not only because there is no tourist infrastructure, but also because it’s impossible to stay here for a long time. Calling visitors to the reserve tourists would be wrong."

In the meantime, we are arriving at the checkpoint "Babchyn". You can only get through by presenting a pass. We quickly have our papers checked and find ourselves in the Zone.

Seeing a two-headed fish is unlikely

Not far from the checkpoint is a scientific facility: laboratories, offices, living quarters and even a small canteen. The reserve personnel lives here on a rotational basis: two weeks in the Zone, the next two -- at home. There's also a museum inside the complex.

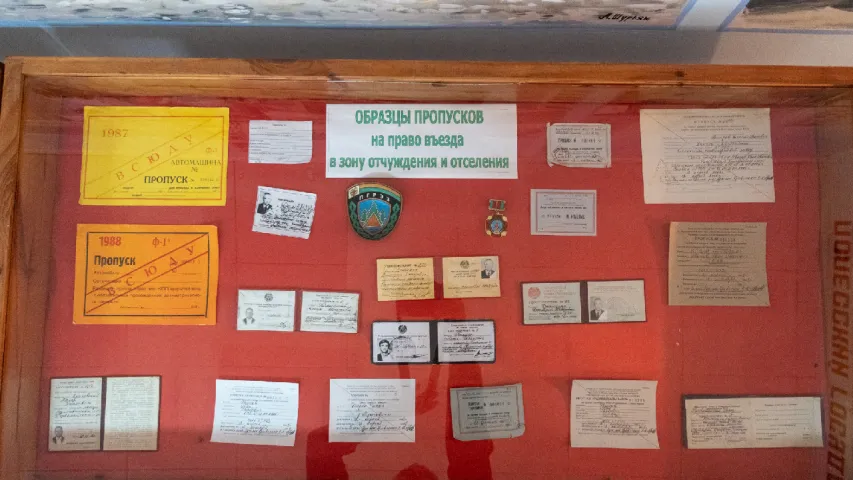

That's where we're going first. The tour is conducted by Dzmitry Ivantsou, a scientist who has been working in the Zone for several years. Lately, he has been studying in-depth the aquatic ecosystem and numerous fish inhabiting the Reserve's territory. The museum consists of four parts. The first hall is a kind of memorial. Various exhibits are collected here -- from the passes of first Belarusian Zone staff to various dosimeters. The walls also have a painting on them -- a large map of the reserve, a list of resettled villages, and the area of lost territories. Everything looks tragic.

The next two halls are dedicated to plants and animals of the Exclusion Zone. Many red-listed animals live in the reserve: from turtles to eagles and lynxes. This is understandable, since the man is no longer the master here, and nature takes over the territory and revives life. But the most unexpected hall of the museum is the last one. It shows the life of ancient people who lived in these places long before the construction of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

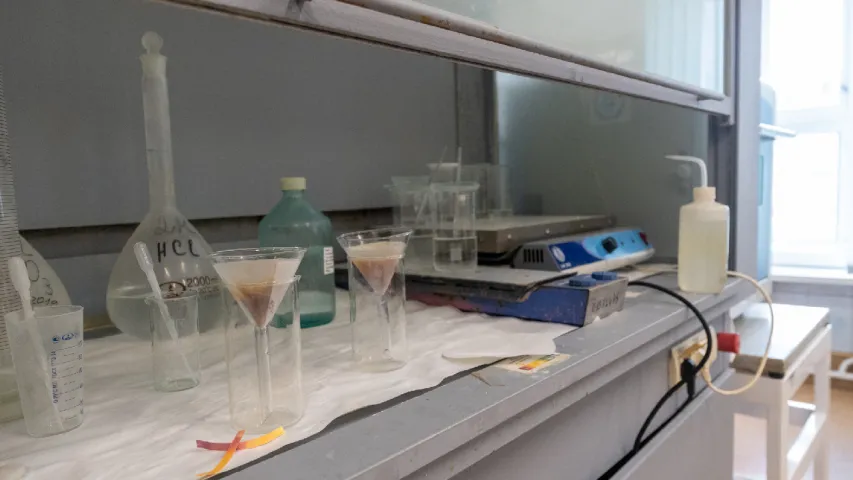

Various research programs are conducted in the science part of the facility almost 24/7. One laboratory can study the radiation spectrum of a single particle, and the one next to it can host an autopsy of the deceased wild boar's rectum. This happens day in, day out. A separate place is occupied by studies related to economic activities in the reserve. For example, here they supervise the wood cutting: they mix the varieties of sawdust, dry, soak, sift, measure the background in different quantities and aggregate state.

The last office we enter is Dzmitry Ivantsou's workplace. Inside there is a distinct smell of dead fish. Looking at the journalist's face, the scientist begins to smile: he had to work with worse smells than that. In the spectrometer next to his table there are pieces of fish caught for measurements.

"You need to know that not only Pripyat with its numerous tributaries and false rivers flows in the reserve. We have here hundreds of kilometers of reclamation channels, which were previously actively used against waterlogging. And now everything is moving in the opposite direction and thanks to such channels a new marsh ecosystem is formed. It's not good or bad -- nature itself regulates the surroundings," Ivantsou says.

The scientist answers a question about the multi-meter catfish that allegedly live near the Chernobyl station.

"Meeting a two-headed fish or something like that is unlikely. In addition, congenital mutations occur without radiation, it is enough to look for such photos on the Internet, and you will see that it can happen anywhere," says the scientist. "My task is to study how radioactive particles can accumulate in different tissues of different fish. And I can say that everything depends not only on the water body. It is clear that the levels in the river will be much lower than in any small artificial pond with no drain. The level of accumulation depends not only on the age but also on the species and even on the sex of the fish. So you don't even know what to expect from each new specimen".

"And the land in the Zone itself -- will it be possible for the people to return here?"

"This is a difficult question. It is clear that plants, animals, and people will get used to any conditions. But it can happen here that something can survive even at extremely high levels of radiation, about 1% of the population of 100. And at low levels, on the contrary, 99% of the population will survive. But who wants this 1% of the population to be human?"

The value of the Exclusion Zone is that we have an absolutely unique "landfill" where nature gains its ground from people. This attracts the attention of naturalists from all over the world -- we have almost a pilgrimage of birdwatchers here. Recently we had even visitors from Britain, who came to visit us and remained delighted with what they saw. But we're used to it -- sometimes you're on a boat, and there are birds of prey flying over the water. And it's beautiful.

The Maidan checkpoint: 30 km to Chernobyl NPP

The tour continues -- we go deep into the exclusion zone. Together with Yury Marchanka, head of radiation and environmental monitoring, we get into the car and travel to the next checkpoint, which is called "Maidan". Behind it are secluded areas. Here begins a 30-kilometer resettlement zone marked by barbed wire.

The officer on duty at the checkpoint double-checks the documents, then opens the gate and wishes us good luck. The car starts rides along the road where the broken sections alternate with the repaired ones. As our guide says, from time to time some money is allocated for road repairs. Then the worst sections are patched.

Our next stop, the village of Pahonnaye, where more than 1,500 people lived. It has its own school, a shop, and a bank. The car stops at a small patch between the "office" and the House of Culture. Nearby is a monument dedicated to the Second World War -- it stands out because the soldiers there have been recently painted, and the site in front of it, apparently, has been recently cleaned. Yury says that the reserve's staff keeps all the monuments in the Zone in order (53 in total). The same applies to cemeteries, of which there are 89 in the Reserve.

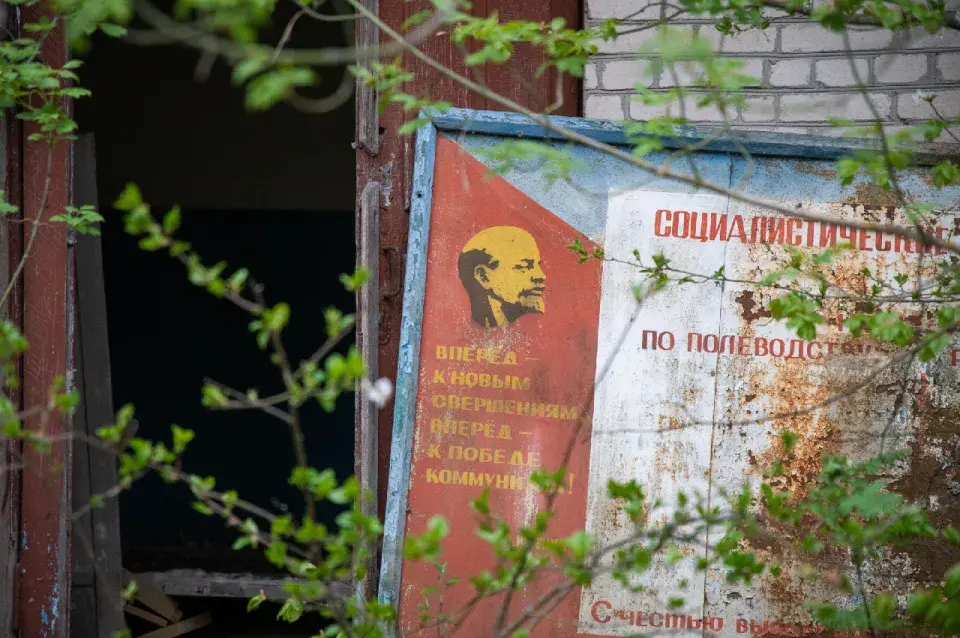

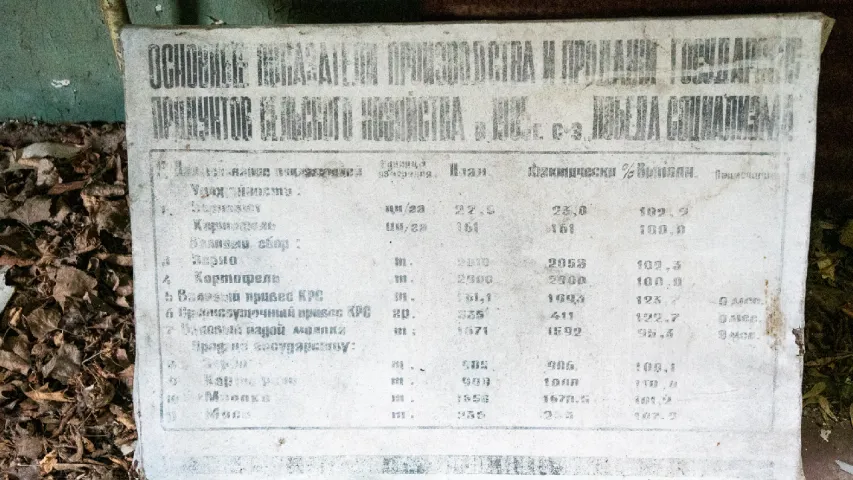

Time in the village really stopped immediately after the evacuation. There are books on the floor of the "office". Bookcases lie overturned. In the corners, there are portraits of Lenin. The building is damp, the ceiling has begun to collapse, and the boards are creaking underfoot.

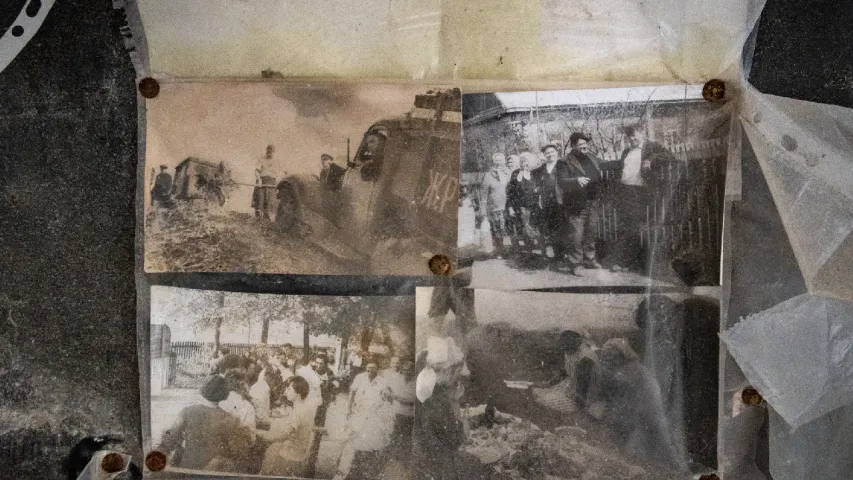

A portrait of Pushkin is nailed to the bulletin board at the House of Culture. Inside there are some old things: black-and-white photos in a file, divided into headings with titles like "Our work", "Our rest", etc. People come here during Radunitsa to visit the tombs of their relatives and to take a walk in the places of their youth.

In the assembly hall there is a scattering of banners, signs and stretch marks. These were either left behind by the local entertainers who were preparing for the Labor Day in April 1986 or stalkers who created a kind of exhibition -- nobody knows. In general, many touching photos with dolls, children's shoes or gas masks of small sizes were taken in the Zone. It is hardly worth believing in such photos: in 99 cases out of 100 they were staged installations, where epics and tragedy were artificial.

However, the real tragedy in the Zone is abundant enough. The school, which is a couple of hundred meters away from the Culture Centre, is run by mice. There are still reagent cones on the shelves in the chemistry room. Hundreds of notebooks, folders, and magazines are on the other shelves.

Nearby are the one-story buildings of the local hospital. It is difficult to approach them: everything is overgrown with bushes and small trees. Inside there are abandoned beds. In the cabinets, there are syringes, ampoules and sealed boxes of medicine. These medications won't help anyone anymore.

Stalker's verdict

The Belarusian Exclusion Zone is very different from the Ukrainian one. There are dead cities and enterprises, abandoned military facilities, which can be reached by hiding from the guards. Here are science and nature. But it is officially available. For a person who saw the "real" Zone and walked on the roof of the unfinished power unit of the Chernobyl NPP, there is nothing to look at.

Nevertheless, some Belarusian "facilities" almost do not differ in ambiance from what can be seen in the dead Pripyat -- schools, local recreation centers, abandoned houses. And they even win in terms of safety -- there were not so many looters and stalkers here, who disassembled the "facilities" for souvenirs.

But if you've never been to the exclusion zone, you should definitely go there. First of all, it needs to be done to go to 1986, to feel the atmosphere. And to see how nature now regains what was once taken away by man. Besides, you may be lucky -- you will be guided by someone who lived in these places during the tragedy and evacuation. Then it is possible to hear real stories, names and even to find artifacts from that time. And it is much more interesting than just looking at abandoned enterprises.

In total, there are 96 abandoned villages in the Belarusian Exclusion Zone. In 1986 more than 22 thousand people lived there. Skeletons of abandoned buildings will serve as monuments to the biggest man-made disaster in the history of mankind for a long time to come.