"Son, I dreamed you were hungry": a volunteer shares messages with his mother

"Mom, I'm fine" / @rubanau_collage

Vital (name changed) studies at a Polish university and lives in a dormitory. His mother thinks he studies at a Polish university and lives in a dormitory.

But a year ago, Vital had a callsign — "Shtanga." He served in Ukrainian intelligence and participated in combat assaults. His mother thought that he was working at a factory in Poland. She thought he wasn't getting enough sleep because he had to wake up early for his morning shift at the factory.

The day before his first combat mission, his mother texted him :

"Son, I dreamed that you were cold and hungry."

He felt uneasy but replied to her: "Everything's fine. I'm going to my first shift."

His mother still doesn't know where Vital spent the past year.

— Yeah, she has a gift. Turns out, I… well, lied to my mom — he finds it unpleasant to say. — I would like to tell her a lot, but I knew it could endanger our family.

But to everyone who knew where I really was, I spoke and wrote as it was: guys, I just got out of a hellhole. But everything's fine.

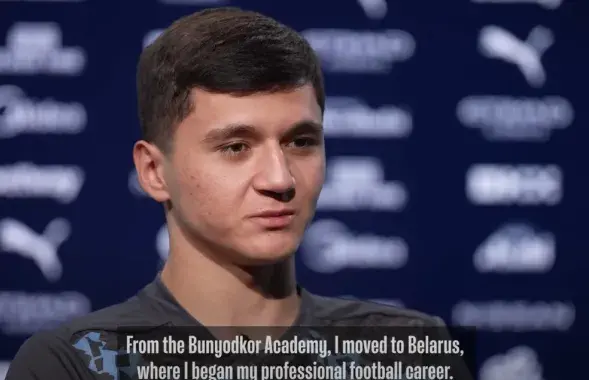

This is the third story from Euroradio's new project, "Son, you good?" Belarusian volunteers and aid workers in Ukraine let you look at their messages with loved ones. And they talk about what they don't say when they answer every question with "I'm fine."

"You come back from Donbas and do homework with some kids."

Vital lives in a student dormitory in Poland. Almost all the guys smoking outside or riding the elevator up and down are about his age. However, for most of them, the most significant change in life was moving out of their parents' house and into this student dorm.

"It's hilarious: you come back from Donbas, and like a schoolboy, you go to class with some kids," Vital says as we go upstairs. "Then you sit down and do your homework. Your mind could break from this contrast. But I find it amusing".

We meet some guys in the elevator trying to pick out chords for Limp Bizkit on the guitar. Vitaliy plays guitar too — he plays "No One Writes to the Colonel" by Bi-2.

Vitaliy lives alone. He used to have a roommate, but he went back to war. Many return to war from peaceful life. "Shtanga" forbade himself from thinking about it and tried not to follow the news from the territories he once defended (all now occupied by the Russians).

— War is like a fast carb. It gives you an enormous rush of emotions — bad and good. You have a vivid, unforgettable life. You have a purpose: to defeat the bastards. And you're surrounded by people who believe in this goal, who do everything for it. Great company; everything is perfect.

Then you come back here and don't understand what you're living for. To make money? To build a house, start a family? And then what? And if you can't find a purpose, you want to go back.

I realized that if I went back to war now, it wouldn't be a heroic act, not an act of valor. There would be nothing noble in it. I would be doing it for comfort.

— Comfort?

— The army thinks for you. It decides where you'll sleep, when and what you'll eat, and where to go. You get used to it, and you feel an enormous emptiness when you leave. An emptiness that many people have nothing to fill with.

"War turned out to be something between 'Cargo 200' and 'Green Elephant'"

Everything "Shtanga" describes is far from what we'd call comfort:

— They dropped us off in the wrong place again. You're standing in the middle of the night in this black soil. And the weather is just fantastic — "plus one": when it's ice, snow, and mud simultaneously. And you just walk through this crap for six kilometers on foot...

To surround himself with such "comfort," Vital dropped out of university, worked side jobs, saved money, bulked up — and finally made it to Ukraine.

— I kind of knew since childhood that I would end up at war. War movies, war games, war books. All my childhood toys — also about war. This path felt predestined.

But the real war turned out to be something between "Cargo 200" and "Green Elephant" [a Russian underground film by Svetlana Baskova. — Euroradio]. It's not about rational things happening; it's complete madness. There was a moment when the Russians found a sewer pipe and crawled through it for three kilometers, like in The Shawshank Redemption, to sneak into the Ukrainian rear.

"Shtanga" might not have made it to the "real war" — he had to break through. When he arrived at the Kalinousky regiment, he waited four months for his paperwork to be processed and just stood at checkpoints.

— Funny: a Belarusian, speaking perfect Russian, without any documents, standing there with a rifle, checking the IDs of GUR officers.

Then came endless duties, and then there was a conflict with the former PKK headquarters. Ultimately, "Shtanga" decided not to wait for HQ to send him to war and transferred to the Second International Legion. Another Belarusian volunteer, August, was serving in this group.

— At PKK, they told us: "They'll send you to the trenches as cannon fodder!" But I have no regrets.

When I was preparing to join PKK, I was running, working out, and passing Cooper tests (tests developed for the U.S. Army). I can do 20 pull-ups with extra weight. But there were a lot of guys there who didn't give a damn about the war—old grandpas who eat fly agarics and can't do five push-ups.

But let me clarify: today's PKK and the old PKK are two different structures. The leadership has changed, and now everything is great there.

— Many would have been happy to just sit it out in Kyiv. Why do you need a "real war"?

— I literally spent my resources and took risks just to get to this war. And I didn't do it to sit at a base. Maybe some people go to war to boost their self-esteem. "I was chewing through tanks like they were candy."

I had different goals. When you're at war or in a combat unit, you're surrounded by such an incredible, pure society. Everyone around you is honest, and you're ready to die for them, just as they're ready to die for you. And it feels like you're in paradise.

And you don't need anything else. The society there is so ideal that you can't trade it for the bored-out faces of Kyiv.

"Well, he's a decent guy. Do you work out? Cool, we'll take you."

Vital's mom sent him pictures of their dog, and he would send her cat memes in return. Meanwhile, he was going on combat missions in Chernihiv and Sumy regions. He served in reconnaissance—meaning he crossed into Russian-controlled territory (he calls it "beyond the ribbon").

— How did you get into reconnaissance? You probably needed a ton of skills for that, right? Where did you get them?

— It only seems that way. I arrived and just talked to a guy.

"Hey."

"Hey."

"Well, you seem like a decent guy. Do you work out? Cool, we'll take you."

After just a four-day course, I became a medic and a field medic for a recon team. And there were guys who, after the same four-day course, went straight to Bakhmut. Time in Ukraine moves very fast.

— Tell me about your first combat mission. What happened when you lied to your mom, saying you would work at a factory?

— Our vehicle got stuck in the mud, and we spent five hours pushing it out.

My first real combat mission — something serious — was my first time crossing the border for sabotage operations on enemy territory.

But honestly, we must have looked ridiculous.

There were four of us. The hardest part of reconnaissance is the mines. The first guy walks ahead with a metal detector and a rifle slung over his back—like a border guard. The second guy had to buy something to mark the path so we could find our way back. He bought yellow and blue flags and marched along like a Dynamo Kyiv fan, waving them around.

I was third, the only one holding a rifle with a grenade launcher strapped to me, choking me. The fourth guy carried an AT launcher, dragging his rifle behind him like an old lady pulling a shopping bag.

That's how we walked. We got in and did what we needed to do. We didn't do what we didn't need to.

Then, when we started heading back, we realized that those yellow and blue flags? Completely invisible. We'd put them down and already lost our way long ago.

— And the metal detector?

— The battery died. So we just had to find our way back by memory. Every step you take, you feel it. It's impossible to describe. It's like walking on a dam, knowing that one wrong move and you're done.

The funny thing about war is that you're not scared when you're actually in danger. You just have to focus and do what needs to be done. But what's really scary? A squirrel suddenly dashed past. You jump up with your rifle, ears ringing from the adrenaline.

Vital says that often, your biggest enemy isn't the Russians — it's Russian artillery. Or sometimes, even your side, because friendly fire is common in war.

— Communication is a mess. Sometimes, our guys returned from a position and got mistaken for an enemy recon group. And then… well, let's just say things got intense.

I've stood under fire from my guys a couple of times. Yeah, it's a funny situation.

We were coming back and saw people at an observation post. We approached, and this panicked guy grabbed his PKM machine gun and started reloading it right in front of us. We were like, "Dude, chill, we're on your side." We knew that if things went south, we'd have to take him down—but obviously, we wanted to avoid that.

So we started naming commanders, looking for someone who had their military ID on them.

— Were there Ukrainians among you?

— Just one. But what could he do? Start speaking Ukrainian? In the end, everything worked out. In situations like that, the key is to stay calm.

— Stay calm?!

— Yeah. Just stay calm.

Either a complete bastard, or absolute good

Vital liked working in northern Ukraine — in Chernihiv and Sumy regions. He says it was a more intellectual kind of war than what came later in the East. In the north, you could at least plan your actions. It was just a meat grinder in the East—whoever throws in more bodies wins.

And he liked the people in northern Ukraine.

— The Chernihiv region is perfect and unique because it's close to Belarus. Some people there even speak Belarusian. You'd be walking, and someone would ask, "Where are you from, guys?" And that's even though we were dressed as civilians and trying not to stand out. But of course, when a group of men shows up at a house near the front line, it's pretty obvious who they are.

I usually joked — "Wagner Group."

There was this old lady, an amazing woman, bless her. She cooked for us. There were a lot of good moments like that.

But in Donetsk, it was different. Some people gave you everything they had, and you always felt like you owed them something in return. And then there were the "waiters"—waiting for the Russians to "liberate" them. Sometimes, you could tell someone just hated you. Once, someone even wrote, "Banderas, F*** Y…" I didn't finish it — must've been a cultured, Soviet-raised person.

War is all about contrasts. You meet people living under shelling, working for pennies to help you. And then you meet complete scumbags. There's no middle ground, no "just an average person." It's either a complete bastard or absolute good.

"After looking death in the eyes, dreams about exams aren't scary anymore."

"Stanga" doesn't openly discuss returning from Ukraine, but his entire wardrobe is camouflage. So, many in his dorm suspect where he spent the past year. Sometimes, they ask him about the war, and he tells them "funny stories"—but no one ever laughs.

— Like what?

"Stanga" tells a story about how, on New Year's Eve, he and the guys got high, and he saw the "hand of death" — a shadow falling over a neighboring Kyiv building. In the morning, a missile hit that building.

He ran to help with the evacuation, breaking down doors with the police. In one apartment, he found a man sitting there, missing both legs. He rushed to apply tourniquets—only to realize the man had lost his legs long ago. It wasn't a war injury.

— I thought we'd all laugh about it. But people just start crying.

Civilians are complicated.

I asked Vital about his plans for the day and what his days were like in Ukraine. He chooses to answer the second question first.

— There, every day is unlike anything else in this world. Every day is… I don't even know how to explain it. Someone does something crazy; you get assigned an interesting task, then there's some drama — someone fighting over a girl, someone finding something—and you all drive out to sort it out. Then you get shelled. It's just constant adrenaline, a flood of emotions.

— And here?

— Here… just routine.

Recently, Vital and his friends went to the Polish mountains. They set up tents—and police officers immediately arrived on snowmobiles to fine them. This European bureaucracy is annoying because just a few months ago, it was "anything goes."

He didn't have a driver's license in Ukraine, but his military ID said "driver-shooter." Even if he got stopped, there was no fine. And even if there was? Vital is a Belarusian and a foreign volunteer. He had no registered address in Ukraine — there was nowhere to send the fine slip.

Now, Vitaliy lives in a student dorm, following an army routine — waking up early, keeping things clean, studying, reading. Filling the emptiness that makes so many of his comrades return to war.

— I love history and wanted to be an archaeologist, but you can study history on your own. My more practical plan is to become a maritime navigator. I'll join the Navy.

— What's that book you're reading?

— Oh, this? The History of Mass Media.

He flips through the pages.

— It explains how institutions are formed. I love philosophy. I used to like existentialists — Nietzsche. But then I realized their ideas are too easy to manipulate. It feels like reading some cheesy street wisdom quotes.

Now I'm into transcendentalists — Descartes and Kant. But Kant is tough. It feels like reading math — constantly flipping back to the previous page. I can't read him in English yet.

I study a lot. Like in school — doing homework.

But back in school, when "Stanga" was still Vital, he had nightmares about failing exams. Now, they don't scare him anymore.

He sits inside the dream and doesn't worry about the exam.

— When you've looked death in the eyes, things like exams don't seem so scary anymore.

Vital remembers school, and I realize he finished it not long ago. He still wonders what his teachers would think if they found out that their former student had fought in Ukraine. He wonders if they would recognize him. Suppose they would notice the changes.

— And your friends — will they notice?

— Friends, friends… You rethink the concept of friendship at war.

— Will your mom notice?

— I wouldn’t want her to see any changes. Let her see the little son she remembers.