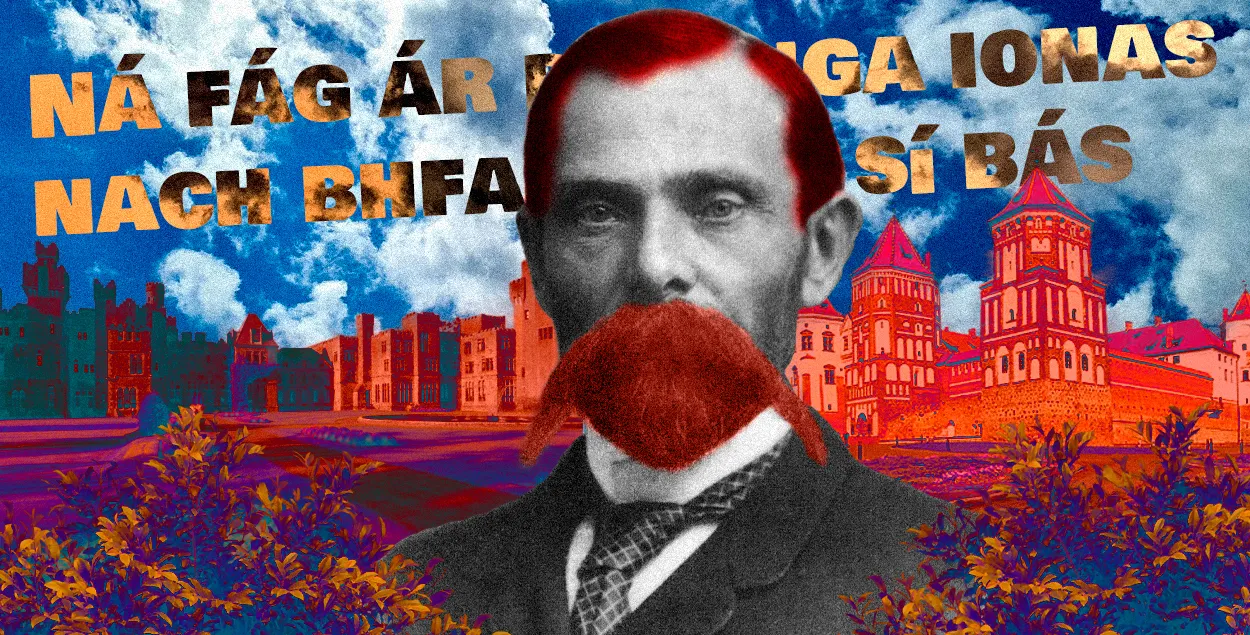

Is Belarus an East Slavic Ireland? "Our language was destroyed 500 years ago"

"No, we don't speak Irish. But if you call an Irishman an Englishman, believe me, you'll get a very quick answer" / collage by Ulad Rubanau, Euroradio

Aliaksandr [name changed] moved from Belarus to Ireland a year ago. I installed the "Duolingo" app and decided to learn a few words in Irish before the trip. I didn't get very far in the study, but at least I was able to say hello to my colleagues in the new office:

"Maidin mhaith", Aliaksandr said.

"What's that?" my colleagues asked.

"They praised me, of course, but said they didn't understand anything," Aliaksandr later told us. "Irish is almost not spoken in Ireland. But sometimes I still write "thank you" in Irish in my work correspondence and get a lot of smiley faces and positive feedback in return".

"Those who taught Irish were killed"

There are more Duolingo users who learn the language than all native Irish speakers. Although it would be more correct to say "Gaelic" rather than "Irish". And if you try to speak Gaelic in Ireland, 60% of the people won't understand you.

But considering what the Irish language has been through, the fact that it has survived at all is a miracle.

"The written Irish language was destroyed about 500 years ago. It disappeared completely. All the books. Everything! The language was rebuilt," Aliaksandr's colleague David Byrne tells us.

David is one of those who not only understands Gaelic, but can speak it. At school he studied all subjects in Gaelic for a year.

"When Ireland was under British rule, it was forbidden to learn Gaelic. If you taught Irish, you could be killed. But many teachers worked anyway - in the woods, away from civilization, illegally. And that went on for three hundred years".

Also the language was transmitted orally, through songs and stories. The Irish are very good storytellers and that helped to keep the language alive. But only the oral language. That's all we have left.

"A movie in Irish is something extraordinary"

Only 7 percent of the country's population speaks Gaelic fluently every day.

"To keep the language alive, you have to maintain it, you have to practice it all the time. Most people in Ireland don't do it".

David's colleague Sarah Hurley, for example, has a Bachelor of Arts, English and Irish. But now it's going to take her a while to get involved in speaking Gaelic -- because without constant practice, even her native language gets forgotten.

"And when was the last time you spoke Irish?" we ask David.

"I said a few phrases a couple of days ago, on Friday. But a full conversation..." David hesitates. "Probably about six months ago".

His other colleague, Edel Greenay, tells us that the last time she used Irish was in Greece. When traveling, it becomes a kind of "secret" language for the Irishman.

"It is very typical of the Irish to "remember" Gaelic abroad. In those moments it turns out to be very useful. And then you come home and forget about it again".

Ian lives in the capital, Dublin. He can speak Irish but he doesn't see the point. The last time he spoke the language was at school. Sometimes at work, in conversation with co-workers, he may insert a few Irish words. But when we ask him when was the last time he had a long conversation in Irish, Ian thinks long and hard. Well, yes, at school. And never after school.

If you want to hear Gaelic, you have to go to the Aran Islands. In other parts of the country, Irish is rarely spoken. But you can see the language everywhere.

As you walk through the city, you'll notice that every English sign is duplicated in Irish. When you get on public transport the stop will be announced in Irish and then dubbed in English. And all government documents are also bilingual.

If you want to go into politics, you also need to speak Irish, because the law obliges civil servants to respond to appeals made in Irish only in Irish.

It seems to Aliaksandr that this "relaxed" attitude of the Irish themselves with regard to the language may be due to the state's concern for it.

"You can see that the situation in the country is not tense, so people are relaxed and do not care so much about preserving their identity through their language. The Belarusians also had a desire to speak the Belarusian language grow in 2020, as a response to pressure from the authorities.

And while on the surface the situations in Belarus and Ireland may seem similar, I see that they are very different. Here, the authorities are interested in preserving the language. It's different here.

"Children are taught to read words, but should be taught to speak"

Sarah did her diploma in Irish. She loves the language, but she also doesn't like the way it's taught in most schools.

"I think it's a very outdated system. Children are learning words instead of learning to speak".

Aliaksandr, the son of a Belarusian, goes to a regular elementary school - and learns Irish. The teacher praises him.

"But they really just read some simple phrases and learn some words. It seems to me that in Belarus, children in the fourth grade speak Belarusian much better than they speak Irish at the same age in Ireland".

But it has to be said that while there are similarities between Russian and Belarusian, English and Irish are two completely different languages. And English is more of a hindrance in learning Irish. The letters seem to be the same, but the rules of writing and reading are completely different.

"Oh, very different!" David and Sarah confirm and name the differences which would require an article of their own to list.

Ian agrees -- it's a very difficult language. And he tells us why many children find it difficult to learn Irish. At least that's what happened to himself.

"We learn the language from old poems. I started speaking Irish at the age of three, in elementary school - and finished at 17. That's 14 years of learning Irish. By comparison, I only studied French for five years. And I still graduated from school with a better command of French than of Irish.

The government declares: it's our national language, we need to preserve it. And that's understandable. But these declarations do not change the methodology of teaching.

But without Irish you cannot get into a good college. You can pass your exams in your major subjects brilliantly, but fail Irish. And miss out on getting in.

And David would like people to love Irish, not be forced to learn it. He recently brought a beautifully illustrated book into the office. It has names of animals in Irish and short stories about them.

"David speaks to us in English, he doesn't impose Irish on anyone, but it's obvious to everyone that he loves it," says Aliaksandr. "It's a very descriptive language, he says. And yes, I leafed through this book: the names of the animals are really very clearly related to the way they behave in nature".

"You understand the country when you understand its language," David explains. "Irish is unique, and it's woven into our culture".

Don't even think about telling me I'm English.

The Euroradio correspondent dares a provocative question: if everyone speaks English, how will I know that I'm in Ireland and not in Britain?

Aliaksandr answers jokingly:

"There will be Guinness ads everywhere, you won't get confused".

And David, Sarah and Edel recommend to avoid asking such questions in Ireland.

"I think if you ask any Irishman if he is English, you'll get a very quick answer," Sarah laughs. - We really don't like it when our popular actors or musicians are called British. And the answer to that is always quick: uh, no, no, no!"

David reminds us of the situation Irish actor Paul Mescal got himself into last month. The BBC mistakenly referred to Paul as British. And a few weeks later, on the day of the British Academy Film Awards, Paul gave an interview in Irish.

He was then praised by Irish writer Eithne Shortall.

"The main reason we don't speak Irish is because we're nervous or a little embarrassed. Probably because we feel: this is our national language and we should speak it more freely," the writer was quoted as saying by the New York Times.

Ireland is now the only EU country where English is spoken. But a year ago, Gaelic was finally made an official EU language as well. Now - almost half a century after Ireland became a member of the EU - all legislation must be translated into Irish, too. This is one of the symptoms of the language's resurgence.

David hasn't had a full conversation in Irish for six months, but when we ask him what his native language is, he answers very quickly:

"For me, it's Irish. And that, by the way, is very Irish. We are proud of our language, and even many of those who can't speak it at all would call it their mother tongue".