War in Ukraine: Refugee stories from the Polish border

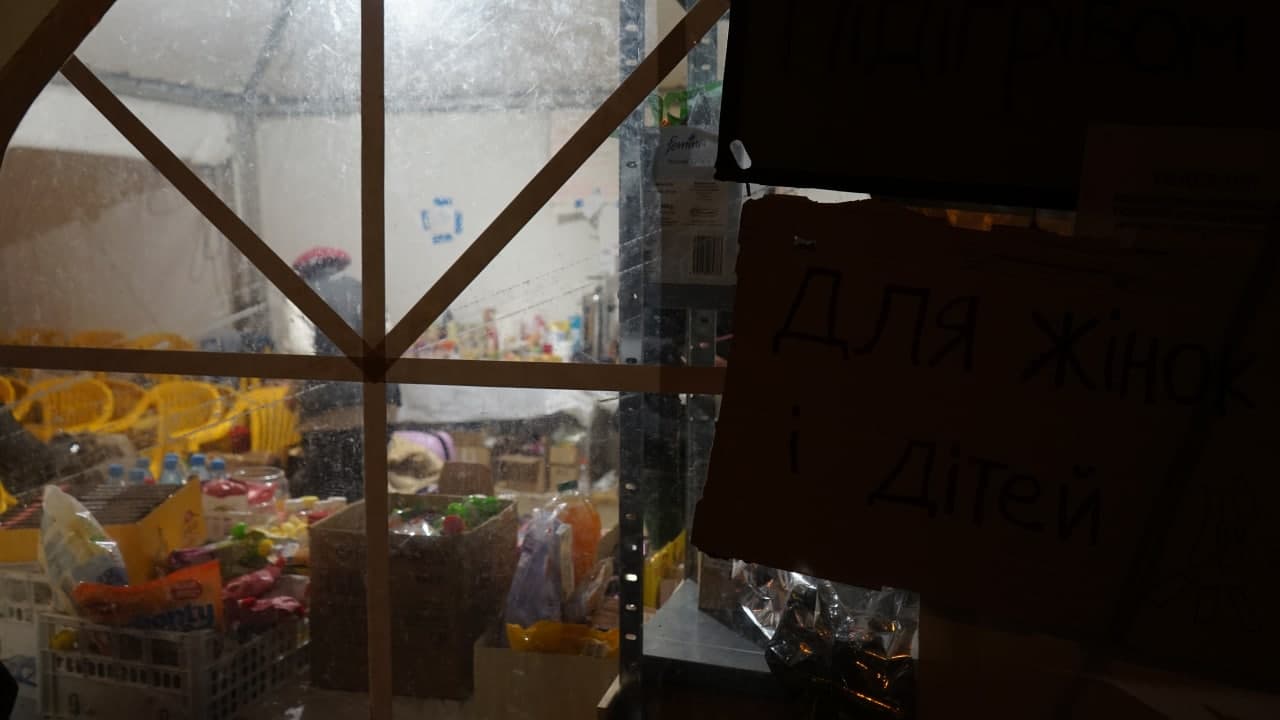

The border crossing point on the Polish-Ukrainian border is the safest distance from which to see the war / Euroradio

Getting from downtown Warsaw to the Hrebenne border crossing point on the Polish-Ukrainian border is easy. One of the many Ukrainians who go there to meet family, friends, and former neighbors will agree to take you with them. Our fellow traveler was on his way to pick up his wife and three-month-old baby from the border.

It took us four hours to get to the checkpoint. For his family on the other side of the border, it was a trip that lasted a few days.

Getting from Hrebenne to Warsaw the next morning would be more difficult. Whichever car you get into, you will feel guilty, because your place in the cab could have been taken by a refugee from Kryvyi Rih or her two daughters.

Ukrainians have to get out of the crowded checkpoints. The rest of the world should make their way there as it's the safest distance from which to see the war.

"That's the kind of cookie my daddy used to give me"

We approach the border. It gets cold as soon as you get out of the car. Hrebenne is a small village near the border crossing. My first thought is that there is nowhere to get warm. There's only one "Bedronka" in the village, and one overcrowded motel right on the border. But the motel had a bar, where you can get hot coffee.

There are almost no refugees at the bar, only people meeting them. Those who cross the border on foot only come here to find out that the nearest bank that accepts hryvnias is in Warsaw. And that they won't like the exchange rate.

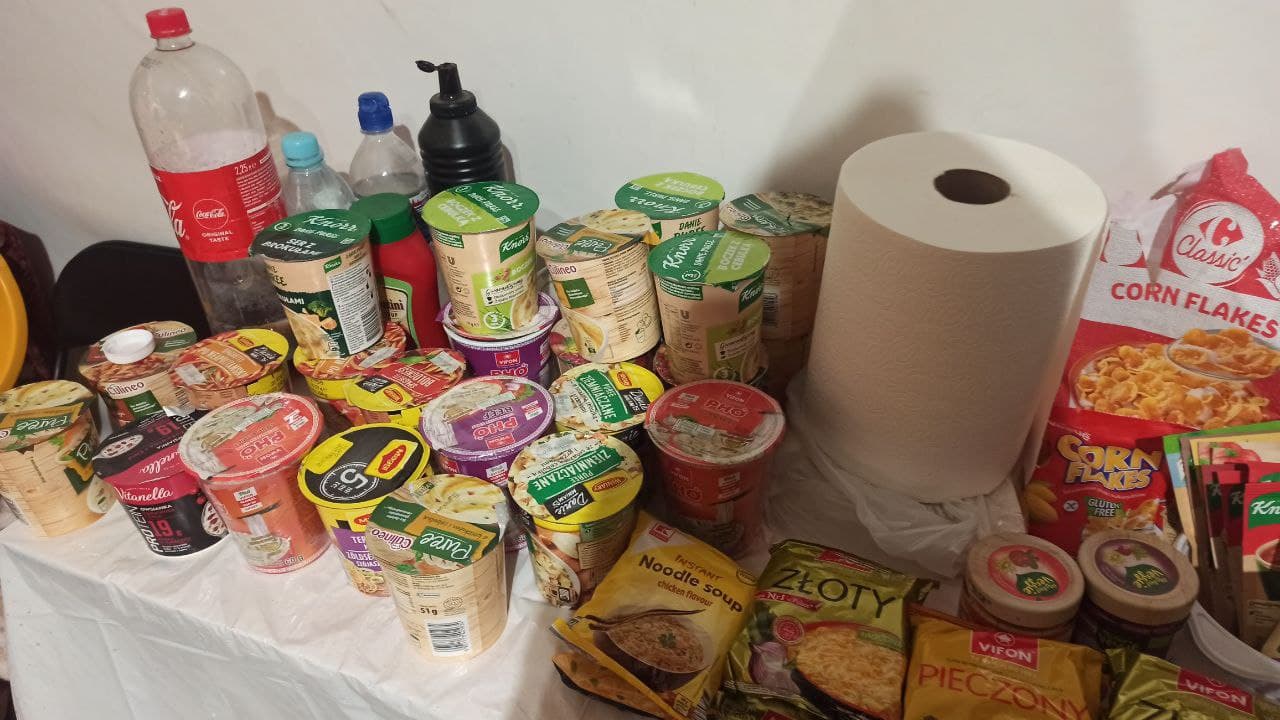

Next to the motel, there are dozens of tents that offer refugees to charge their phones, food, plaid blankets, warm clothes, medicine, toys for children from the humanitarian aid boxes.

We discussed it with each other:

"Looks like the place outside the Akrestsina jail in 2020, right?"

"A little bit".

The mood of the volunteers is also similar to that of the Belarusians in 2020.

"I've never been so proud of the people around me. Such solidarity. I didn't expect us to act like this," says Tomek, a Pole. He has a car and helps people get from the border to major cities

Sixteen-year-old volunteer Staszek gets a call from his parents, asking if he's okay, if he's eaten, if he's not cold.

"I don't think it's me you need to worry about. I will not forget the little Ukrainian girl to whom I gave cookies. She said that was the kind of cookies her daddy used to give her. It was hard to hear that".

It was hard because only women, children, and elderly people can cross to the Polish side. Fathers, husbands -- almost all of them stay in Ukraine.

"I don't know Ukrainian, but I can make soup"

There are several large tents here, with heat guns running. Next to one of them, two types of strollers - baby and wheelchair - are arranged in two rows. Here, in the warmth, women feed their infants. Some are eating dinner, others are napping or feeding a cat.

Two French volunteers, Victor and Marty, are peeling sausages. Two of the sausages are given to Ukrainian boys about five years old who are hanging around. The rest are crumbled into a large pot of soup, a traditional Polish zurek.

"On February 24, I woke up, switched on my phone, and saw that the war had started. It stunned me. Three or four days after the war started, I came here to the border. I can't stay indifferent, can't do the things I've always done. I don't often speak with Ukrainians. I only speak French and a little English, not everyone understands me. But I do what I can - I make soup. Here, take a look".

Victor opens the lid of a huge pot. Standing next to the hot soup, you remember again about the cold. But before you can complain, a volunteer car pulls up next to him. A young woman and a child get out. They have four carriers with cats in them. An older woman remains in the car and they move her to a wheelchair.

Guilt displaces the feeling of cold.

"I'll send my mother to my sister's - and back to Kyiv"

"I came from Kyiv, I brought my mother, my nephew, and four cats. I am a journalist, I wrote about culture, but since the first days of the war I have worked with the news," says Yulia.

Her mother, Anna Ivanovna, was five years old when the Great Patriotic War began. Now she is 86 years old, she can hardly walk. Every half an hour shells fly over her city.

"Mom was born in the village of Sedniv in the Chernihiv region. Now Sedniv is occupied by the rushists. When it all started, my mother remembered the war. She remembered how in her childhood, during a bombing in Zhytomyr, she got wounded by the shattered glass. She remembered walking with her mother from Zhytomyr to Sedniv".

Before the new war started, Yulia and her mother lived near the Kyiv TV tower. Yulia wasn't going to leave the city, but when a missile flew over her house, she was too scared. Not for herself, but for her mother.

"Missiles can ow be heard flying every half hour in Kyiv. They are being shot down, but it is very difficult to understand whether it was a missile that hit the city or whether it was shot down by the air defense system. I wouldn't have left if it weren't for these explosions. My mother is not a walker, and we couldn't go down to the bomb shelter. So my mom slept in the hallway the whole time, and I hid in the bathroom".

The tent was warm and had everything we needed: food, baby food, and even cat food. Max, Mariaca, Koshmarka, and Basil are safe now, too.

Yulia doesn't need safety. She'll send her mother to her sister in Israel - and then she'll come back to Kyiv.

"I would like to volunteer, to do some good, but I couldn't do it while my mother was at home. If something happened to me, no one would come and rescue her, no one has the keys".

"I'll stand here until they come"

There are bonfires burning along the road, people standing in groups around them. Most of them are Ukrainians who are waiting for their loved ones.

"My daughter and her granddaughter are on their way from Dnipro. It's not so bad there yet. Only the sirens are howling. There is no food in the stores. My daughter was going to come here, she was going to come by plane. She was supposed to be here in two weeks. I told her to come soon. She said, "Mom, come on. Nothing's going to happen. I can't bear to think about it, about how they're getting there now. On that stupid train. The train broke down. It didn't make it to Lviv. They took a cab or something and got off at the border. That's where they're standing with a little kid. Two years old. My granddaughter is hysterical. You can't even see the border. They've been standing there since morning. I don't know what to do anymore".

"How long have you been standing here?"

"Since lunch. The girls drove me from work. I work at the school. The girls brought me here".

"There's a café around the corner. Why don't you go get warm?"

"No, I'll stay here until they get here".

"We didn't want to leave. It's a shame to leave the house like this"

We go back to the motel bar. Here grandmother had just joined her granddaughters: she had been at the bar since the morning. Now she's telling the girls how they'll love going to a Polish school.

It got dark, and there were still a lot of people at the border. As night falls, they will remain there.

When newcomers enter the bar, the people at the tables cheer up. No one asks each other where they come from or who they are waiting for unless journalists do. But if the question is asked, everyone listens to the answer.

"We are from near Kyiv. North direction. We spent three days on the road," says an older woman.

Everybody sighs - everyone understands.

"You could not get out all these days?"

"We did not want to. Because it's a pity to leave the house like this. I have a small dog in my house, a stray cat and a stray dog. So I gave the cat to the kids. The kids didn't go. And I asked the neighbors to look after the dog. And the flowers? I recently planted lilies of the valley along the fence. Everyone told me I shouldn't have. Who plants flowers along the road? And now they dug a fortification in the place of my flowers. Right in front of my house.

"I wait for whoever comes. My family is in Kharkiv"

People stand along the road to make sure they don't miss when their loved ones cross the border.

"Are you waiting for the relatives?"

"No, my relatives are in Kharkiv. I want to give help to anyone who needs it".

Volunteer drivers have to register with the police. There's a memo on the tables in the bar: what to do to not become a victim of human trafficking.

"Wroclaw! Two people! Who needs a ride?"

On this side of the border, no one is crying, everyone is packed: both refugees and volunteers. People answer simple, understandable questions: where are you going? Do you need a ride? What help do you need? Do you want tea or something to eat?

Journalists do not know how to formulate questions the way volunteers do. And when refugees answer the questions like "Who are you waiting for? Who have you left behind in Ukraine? Do you have a place to stay? What will you do in Poland?" they cry.

"I'm traveling from Poland to Germany," Ukrainians say discussing the routes in line for the bus. This bus does not go to Germany, but to the nearby town of Lubcia Korolewska. People will be able to spend the night at the local school. "There are more opportunities in Germany, so I want to go to Germany. But in fact, I want to go home, not to Germany".

"You want to go home? So you must be from Odesa!" the volunteers in the queue guessed.

Volunteers pick up refugees almost as soon as they cross the border during the day. Volunteers offer those waiting for a bus not to stand outside, but to get warm in tents or at least in their cars. But by nightfall, many drivers will be gone. There will be less and less room in tents by the middle of the night. People will be fed and given coffee. If refugees have pets, they'll be fed too - but they can't all get to the night shelter.

"What are you singing?" - "Just nah-nah-nah-nah"

The children are crying, they are tired. Many of them have been on the road for three days, some for five. Their mothers are tired, too, and the volunteers rock them in their arms and strollers, singing songs in Polish and in the universal language everyone understands.

"What are you singing?"

"Just nah-nah-nah."

Some kids want sausage, some want toys, some want nothing.

"How about another blanket? Maybe some tea? How about a meal?"

A girl of about twelve, who spent five days on the road, getting out of Kryvyi Rih, speaks so quietly from under the plaid, which she covered her head with, that you can hardly make it out.

Her sister cries. Her mother agrees to take the tea.

"We're told an evacuation bus will leave from here. Do you know what time?"

"First they take women with very young children. Then the older ones. Unfortunately, you have very little chance of getting there today. Get warm," one of the volunteers explained to the woman and her daughter. "Get warm, feed your children, calm down. As soon as possible, I will get you out, but I will do it tomorrow".

The woman, her two daughters and dozens more refugees will stay in a heated tent at the border until morning.