Back to USSR. What does the Soviet Union mean to those born when it collapsed?

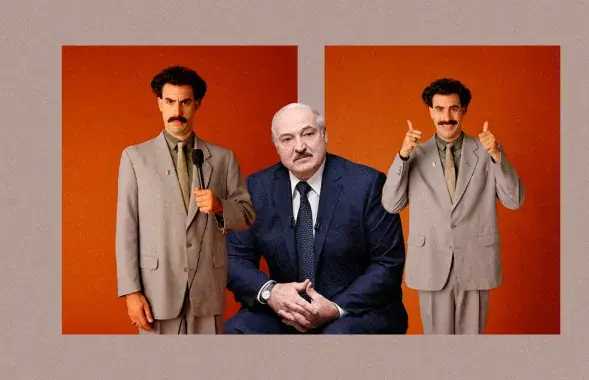

Do the 30-year-olds feel nostalgic about the USSR? / collage by Ulad Rubanau, Euroradio

The Soviet Union ceased to exist on December 8, 1991. The papers were signed in Belarus, in the Belavezhskaya Pushcha National Park. The agreement delicately stated that the USSR ended its existence "as a geopolitical reality and subject of international law." As if those who signed it, namely, Yeltsin, Kravchuk, and Shushkevich, knew back then that the USSR would remain a reality for millions of people for years to come and stay a part of their everyday lives, culture, and mindset.

"Both locals and visitors often call Belarus "the USSR in miniature." Some say it with gentleness, some – with vitriol. Not everyone is happy that the Republic of Belarus looks like the most soviet of all post-Soviet states. Someone who never lived in the USSR would also say that.

Euroradio talked to the agemates of the USSR collapse. Do those born in the 90s get nostalgic about the country they only know from movies and their parents' stories? Some want to go back and consider themselves USSR citizens. Others of the same age, on the contrary, see it as a relict to forget as soon as possible.

Times were more challenging but never as ignoble

Aliaksei, 30, calls himself "one of the last citizens of the Soviet Union." Then adds that he treats the state collapse as "yet amother tragedy of our folk.".

When asked what he means by "our folk," he smiles and says:

"We are the Slavs. As a result of the Great October Socialist Revolution, a new folk appeared – the Soviet people, meaning those with the principle of internationalism. All people are equal," he elaborates.

According to Aliaksei, today, all nations are divided. And the only "united one" consists of those who witnessed the USSR and remember living in it. Then, how did it happen that Aliaksei, who wasn't around back then, considers himself part of "the Soviet folk?"

"I started feeling like I was a Soviet man somewhere in high school. It happened when I started learning history in-depth, especially the period of the Great Patriotic War, watching Soviet movies and reading Soviet literature. It cultivates your personality. When you embrace all of it, you can no longer say you're not a Soviet man."

Aliaksei speaks fondly of Soviet achievements. It shows that he came prepared. Interestingly, his social media alter-ego is Vasily Zaitsev, a Soviet sniper.

"Before the revolution, about 80% of people were illiterate. But by the time the USSR collapsed, we became one of the greatest nations of readers. And how noticeably did the quality of life improve! The last famine we had was in 1946. And it only happened because they didn't have time to discharge a certain part of soldiers to get them back to work, and, as a result, they failed with the sowing season. Mind, they had famine every three years like clockwork in the Russian Empire," he recounts.

Aliaksei pauses and then adds:

"I think the society was more just back then. I once saw a photo from the 90's rallies where a senior citizen stood holding a banner that said: "Times were harder but never as ignoble."

He agrees that today Belarus is the most Soviet of all the post-Soviet states. Has anything good survived these days? According to Aliaksei, the list includes health care, strategic state-owned industrial giants, and the system of education.

Is there anything else Soviet we should be thankful for? Aliaksei is adamant about Belarusians as a whole being indebted to Vladimir Lenin.

"Pro-democracy liberals don't like Lenin, for some reason. But it was he who gave the nations the right to self-determination, which led to us getting our institutionalized state language. We were recognized as a separate nation and, essentially, given our own country."

Were there any drawbacks? Aliaksei admits there were "overkills." But he's very cautious while speaking about Stalin's terror. He says, for example, that he's never seen any documentation concerning Kurapaty and can't judge whether the Soviets were executing political undesirables here or not.

"Those who believe the USSR to be a good thing and Stalin not to be the worst person ever do not deny there were overkills and people wrongfully punished," says Aliaksei. Then he adds with a smile that he wouldn't want to end up in the USSR during the times of terror, but other than that, he would gladly spend his life here.

"It would be fascinating to see how the Soviet Union started off and then live to see its collapse. To witness all of the changes, to participate, perhaps, given a chance. I think no one sane would want to live during comrade Stalin's day with the purges and excesses. Would you want to live during the Great Patriotic War? No, of course not. It's frightful and terrifying. To me, the best and most nice period is Brezhnev's stability that people now call stagnation, that's for sure. Those were the most peaceful times."

You didn't have to think for yourself that much

Alena Zhivaglod is not one of those who are bitterly critical of the USSR and considers everything related to it bad. However, her point of view is a polar opposite of Aliaksei's.

"I treat the Soviet Union as the past. As a state that, I think, was built and made to function in a way that was to halt the personal and economic growth, human potential, literacy, and education levels. A state where the republics' sovereignty was mostly ceremonial."

What else was wrong with the Soviet Union? Alena lists Stalin, state-controlled economy, censorship, and people's distrust for each other at once. She wouldn't want to live in such a country.

"I like to ask my friends what era they would go back to? Definitely, not the USSR. Perhaps, it's because I've heard a lot about it from my parents. So, no, I wouldn't want to go there."

Alena's skepticism about the USSR does not come from anything personal: no one from her family was victim of political repression. She says she's being rational instead of eating up "spook stories that form the attitude."

To her, Belarus circa 2021 and the USSR have a lot in common. And not the good things, unfortunately.

"Now we're all thinking about Stalin, drawing parallels. I do not consider it populism to talk of the Iron Curtain, either. These spook stories from 1937 are closely related to what we now have in Belarus. Censorship, repressions, people disappearing, living in fear, and our country's future with Lukashenka is where I draw parallels between the Soviet Union and us, unfortunately."

Alena says that Belarus was "Soviet" even before 2020, but she's also sure that our country was on its way to overcoming this "disorder."

"It is first and foremost about the economy and the closed nature of the country, I guess… It seems Belarus is very slow about becoming a self-sufficient country. Slower than desired."

Unlike Aliaksei, Alena doesn't consider access to health care or education a handsome legacy of the USSR. That's why:

"I think, there's this feeling in the air, strengthened by Lukashenka's regime, that the government's concern for the individual, for the citizen is, well, heightened. Free health care, free education – everything that people seem to associate with the Soviet Union. I'm not one of them. It is how those in power condition Belarusians to feel obligated to the state for their opportunities. It runs contrary to my views about civil society and how the ruling establishment should talk to citizens."

The Soviet heritage that Alena sees as positive mostly resembles something you'd find on an idyllic old postcard or a Norman Rockwell painting.

"I used to bring my foreign friends to see the main department store called GUM when I visited Belarus. The paper they're wrapping the purchases with is the legacy that doesn't repulse me. It is nice how you can literally touch the Soviet Union. Or, say, the Central supermarket with its cafeteria in downtown Minsk. That's as a symbol of the city as the Pobeda (Victory) cinema.

Why do people who never lived in the USSR love it and reminisce about it? Alena thinks it might be because Soviet cinema and literature paint a pretty picture. Aliaksei listed precisely that as a reason for his interest in the era.

"A stability and prosperity of sorts. Everything seemed smooth, polished, and stable, thanks largely to the lack of information. Nostalgia for the Soviet Union is yearning for the time when the state gave you comforts and cared about you. Perhaps, I'm exaggerating. I still think it's about not having to think for yourself that much, not having that much autonomy."

Produced with support from the Russian Language News Exchange